Newsニュース

THE MYTH OF FINTECH DISRUPTION

Rather than disrupting finance, fintech will offer plentiful chance for open innovation with established players. London leads the way. The shape of things to come

Fintech (financial technology) start-ups, combining IT and financial services in new ways, are said to be the disruptors of finance – what Uber is to taxis and AirBnB to the hospitality industry, the likes of Lending Club (link) are to banking. This analogy is flawed, however.

Rising interest

It is getting a lot of traction nonetheless. Martin Wolf, the Financial Times’ leading commentator, dedicated an entire column to the topic this March, explaining how fintech will disrupt finance. At the World Economic Forum, the fintech session was in such strong demand that it had to move venue. A list of prominent bankers leaving finance’s most prestigious institutions to join fintech start-ups just adds to the belief that fintech is approaching its event horizon. The latest convert is Anshu Jain, who left Deutsche Bank after a brief, unsuccessful and stormy stint as co-CEO, for SoFi, a fintech start-up from Silicon Valley.

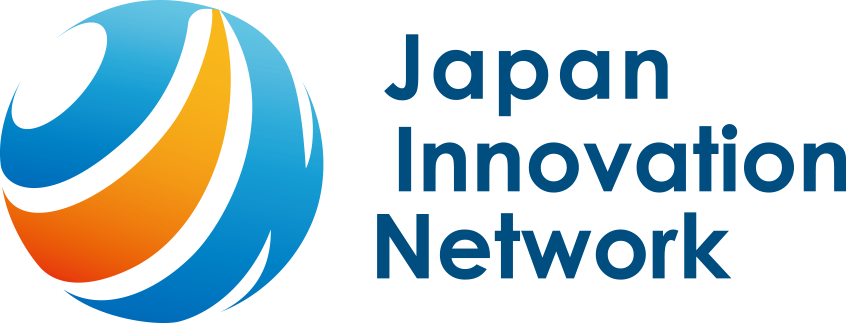

Cities around the globe are stepping up their efforts to become the world’s capital for this fledgling industry, too, with London and New York in the lead. This rising interest is reflected in the stellar rise of fintech investment, which has tripled from 2013’s $4bn to $12.2bn in 2014 (see chart below). KPMG, an accounting firm, estimates that it has broken the $20bn mark in 2015. Thanks to its financial firepower, America’s fintech sector is the world’s biggest by a wide margin.

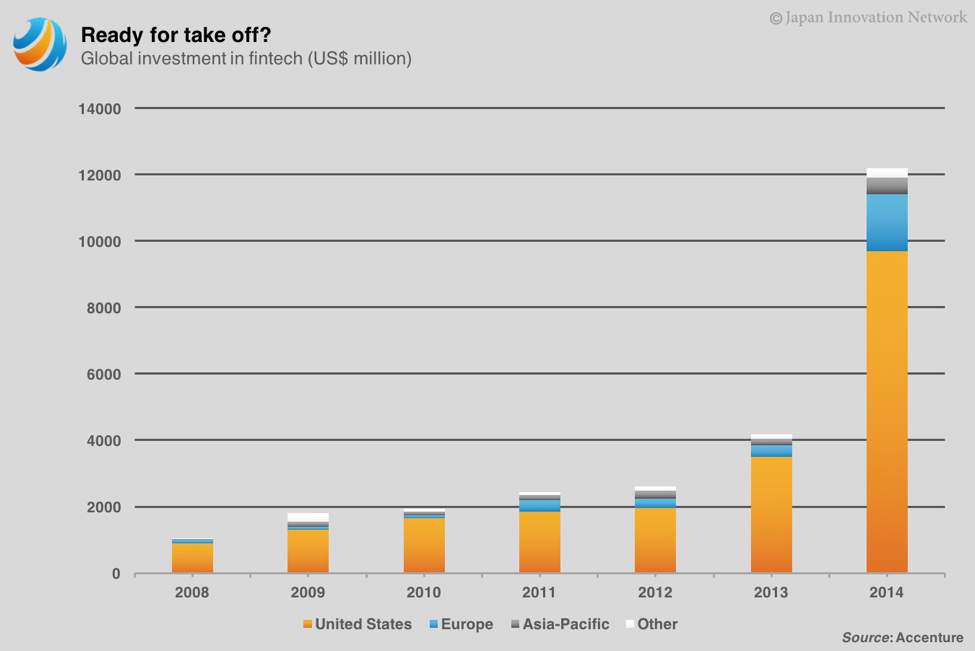

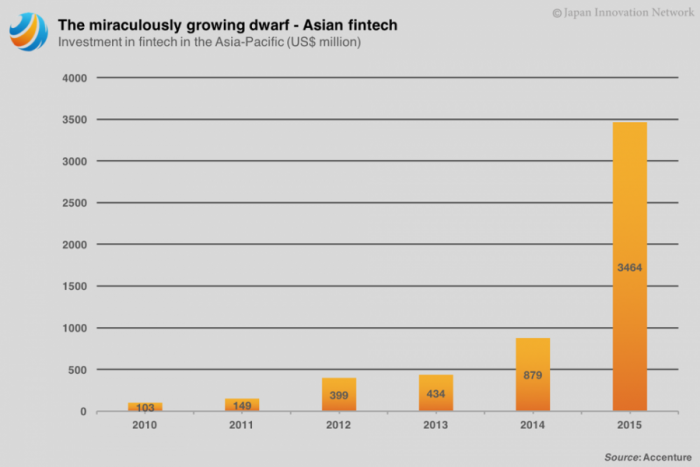

But other economies are entering the contest, too, with fintech investment particularly in the Asia-Pacific skyrocketing – but it is still too miniscule to pose a threat to New York or London for anytime soon (see chart below). China is the most serious Asian contender, having two firms in KPMG’s Fintech Company Top10 in 2015, versus three US and two UK firms. But China’s restrictions on capital movement and its credit-bloated financial sector impose narrow constraints on how big a role China can play globally for the time being. If it plays its cards right, Japan, with its rich deposit base, its strong retail banks and its IT-savvy consumer base, could become a stronger contender – at least for the pole position in Asia. So far, however, regulatory hurdles severely limit its ambitions. With the Bank of Japan just having announced its intention to set up a fintech office, Japan is starting to enter the game seriously only now.

But the sector’s growth is strong in the UK, and from a far bigger base, making it by far the biggest fintech market behind the US. On a city-level in particular, London has the clout to be a top contender for the pole position.

Rising city

London’s fintech sector is well-placed to take on its global competitors. The UK is home to 251 foreign banks and is the world’s number one when it comes to lending and borrowing as well as cross border lending and borrowing. The UK is also ranked number one when it comes to foreign exchange turnover. The City enjoys strong backing from the government in bolstering its attractiveness. The finance ministry even created the position of UK Special Envoy for Fintech, currently held by Eileen Burbidge, to help attract start-ups to Canary Wharf (link). This all makes London a prime destination for fintech. 135,000 employees are already working in the sector, which has revenues of about £20bn (約3.7兆円) and is posting strong growth rates. Level 39 (link), a leading hub for fintech start-ups, is bursting at the seams.

Rising risk?

But far from start-ups alone, London’s fintech scene is increasingly also being shaped by large banks entering the fray. Rather than incumbents whose business is being destroyed by new entrants, they are co-drivers of the phenomenon that has the potential to benefit them hugely. Deutsche Bank is setting up one of three innovation labs globally in London (link), focusing on fintech for the non-retail banking sector – in cooperation with start-ups rather than in opposition to them. Commerzbank and Barclays are amongst those following. The shape of things to come will likely see London as a centre of large bank–start-up collaboration, rather than a fintech warzone.

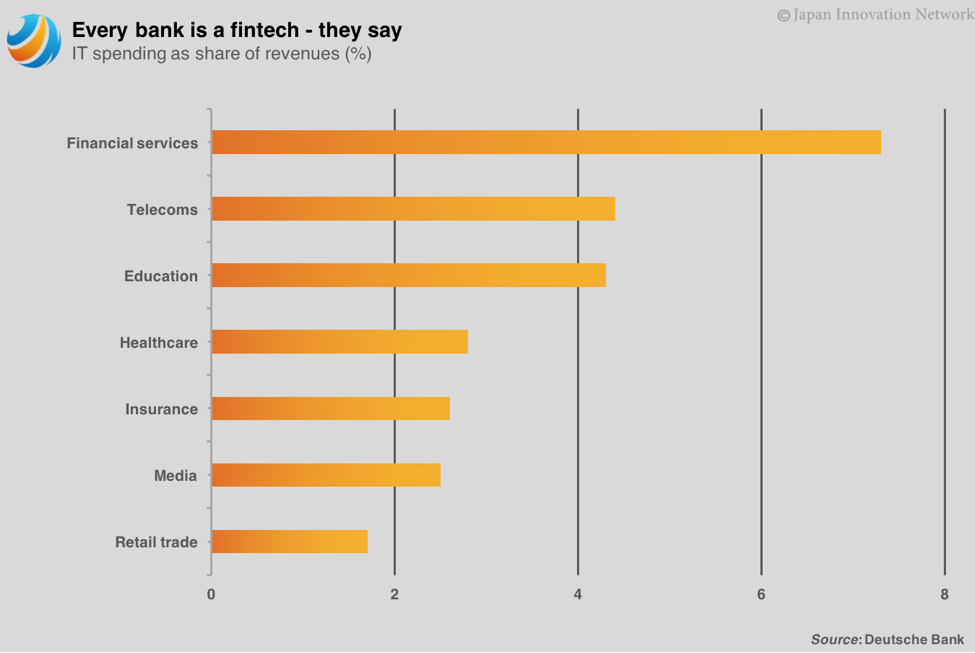

There are three factors that make this outcome likely, setting apart banking from other sectors facing disruption by entrepreneurial innovation: first, banks may be centuries old institutions, but they have been eager adopters of IT services. The finance industry is in fact outspending all other major industries in IT (see chart below). Disrupting this rather solid fundamental will take a lot more than it did for Uber and Lyft to shake up the coddled taxi industry.

The second difference is that many fintech start-ups are seeing their business model in those that have actually fallen through the net of ordinary banks – such as young people or students, all of whom find it difficult to secure loans via the banking system. The German fintech Kreditech (link), for instance, targets customers without a credit history who would stir little interest in a Deutsche Bank investment shark. Rather than vying for the same piece of the cake, then, much of fintech rather is about finding ways of growing the cake.

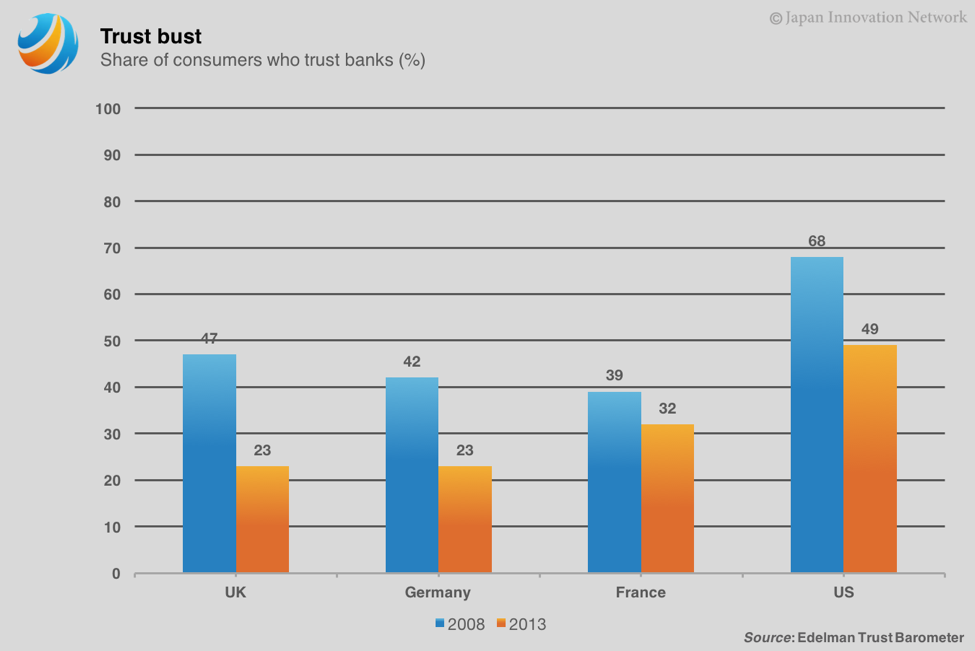

This has to do also with the third and biggest difference, the high barrier for entry to the insurance and banking sector. And this does not only refer to regulatory hurdles that will significantly slow down any potential disruption, but particularly also the high level of trust and credibility that any new entrant needs to secure before they can hope anyone entrusting them with their money. That is why we see most fintech start-ups tying up with a big name player before they can hope to achieve anything in the financial sector: CompareAsiaGroup (link), for instance, one of Asia’s biggest fintech firms, has enlisted the cooperation of some of the world’s major banks – and its founder went on record saying how their business would never work without their backing. If tech really wants to go together with fin, they need the cooperation of big banks. Conversely, big banks could do with better customer service – something most fintech firms peddle as their key selling point – and improved customer satisfaction: big banks have suffered a catastrophic loss in confidence in the wake of the financial crisis (see chart below). And with ultra-low or even negative interest rates becoming the global norm and squeezing banks’ profits, unearthing new business will be vital.

Rising opportunity

This all creates plenty of opportunities – and need – for cooperation. Open innovation rather than disruption will be the guiding methodology of innovation in the fintech sector. Fears of the banking industry being disrupted like the taxi or hotel industry are overblown. The analogy from fintech to Uber or AirBnB is thus a wobbly one. If handled well, fintech will grow the pie for new entrants, and for incumbents will improve service and product offerings and help established banks get their hands on innovative ways of soaking up big data as well as bolstering their customer service.

Anshu Jain may have left Deutsche Bank, but he will find that the walk from Deutsche’s London office to his new fintech office will be a lot shorter than he will have hoped it would be.

By Markus Winter (link)