Newsニュース

THE SECOND COMING – JAPANESE FIRMS IN SILICON VALLEY

Japanese firms have been in and out of Silicon Valley since the 1980s. Now they are flocking to Silicon Valley again – but this time with different ideas on how to make better use of their presence there

Japanese firms have long been an active component in Silicon Valley, since JAFCO opened its branch there in 1984. The first wave, led by firms like Sumitomo’s venture capital arm or Panasonic Ventures, entered the bay area in the 1990s during the height of the IT boom. Since then, most major Japanese household names have joined the fray – from ANA, Sony, Nissan, Mizuho, Hakuhodo, or Omron to the Isetan Mitsukoshi department store operator.

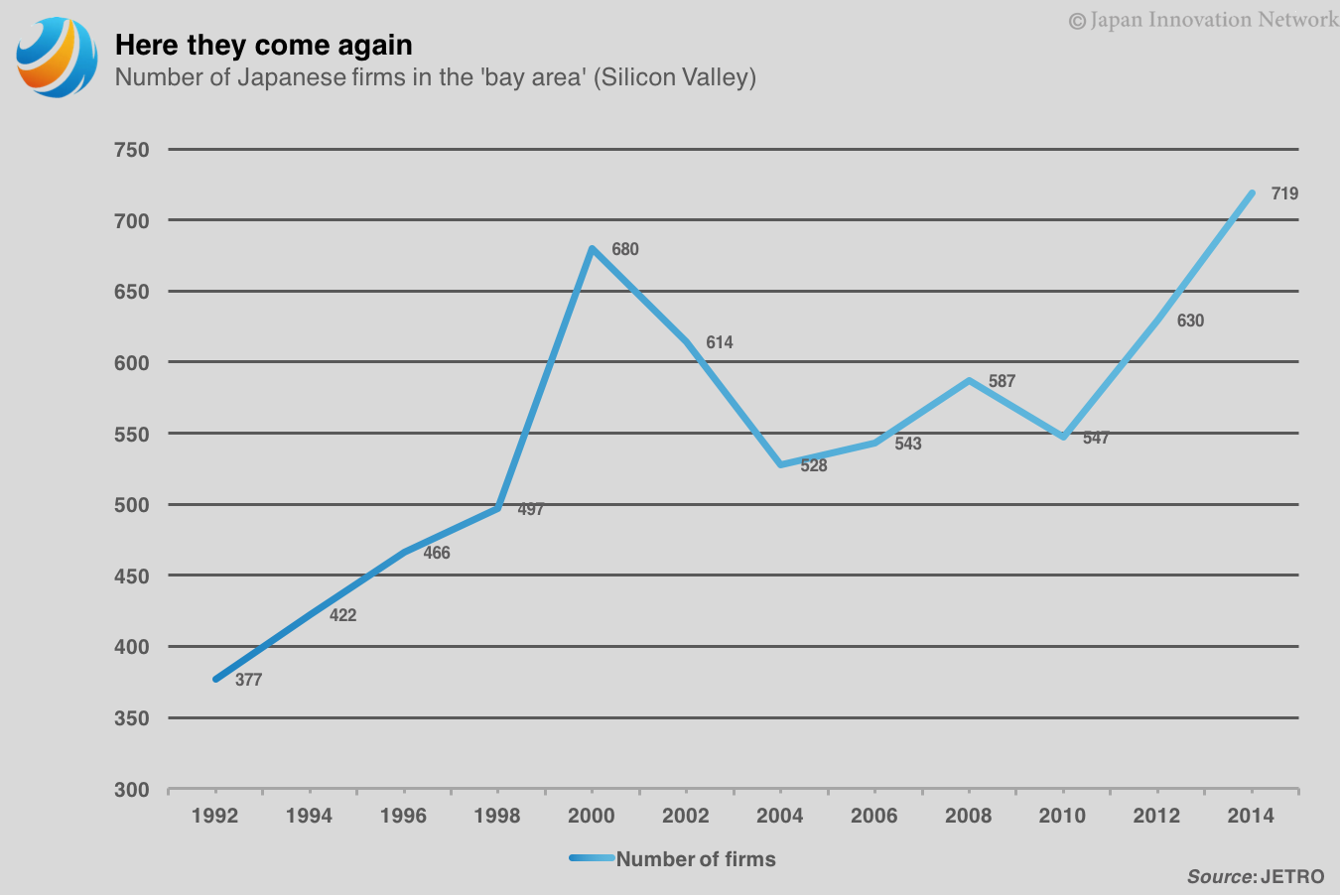

Now we are seeing a second wave arriving: DoCoMo, a large telecoms provider, for instance, opened its doors in 2005; WiL set up its $400m fund in 2013; Konica Minolta is locating one of its five new Business Innovation Centres there; and Yamaha opened its Silicon Valley R&D centre in 2016. They are part of a growing tide: in total, 719 Japanese-affiliated firms (meaning firms founded by a Japanese national, subsidiaries of Japanese firms, or firms whose shares are at least 10% owned by a Japanese investor) have been counted by the Japan External Trade Organisation, JETRO, in 2014.

This second wave of Japanese firms differs from previous entrants in three significant ways: First, simply by number – the 719 firms counted by JETRO in 2014 set a new record. Never were there more Japanese firms active in Silicon Valley, not even during the height of the IT bubble years (see chart 1).

Chart 1

What is more, the pace at which Japanese firms and start-ups are riding the wave is increasing rapidly. 2014 set another record, seeing 26 new entrants from Japan (see chart 2). This trend has been accelerating as innovation management is gaining traction in Japanese boardrooms as the key issue defining a firm’s competitive edge. And looking at the latest (above-mentioned) news reports from big name Japanese corporates opening up shop in Silicon Valley, there is nothing to suggest that this trend will ebb down anytime soon.

Chart 2

Second, the first wave was made up mainly by manufacturers (and of course IT firms) opening branches there. Today, by far the largest group of Japanese firms in the bay area are service sector firms (see chart 3). Mostly it is services in healthcare, education, leisure, and specialised businesses – with IT services only making up one fourth.

Chart 3

This matters. Japan’s economy is often said to be too reliant on the manufacturing. Returning to Japan with their innovations made in Silicon Valley, these firms have the potential to help disrupt Japan’s service sector and close its productivity lag to its OECD peers. Whether this will be the case, however, depends on how firms will use their presence in the bay area. According to JETRO, only about 20% of Japanese activity in the bay area is by Japanese nationals founding start-ups there – most of which eventually also want to do business in or with their home, as for instance Fujiyo Ishiguro has done, the founder of Netyear (disclosure: Mrs Ishiguro sits on the board of Japan Innovation Network); most Japanese affiliates, however, are dependencies of large Japanese companies. Therefore, much of the innovation from Silicon Valley dependencies will only have an impact on big Japanese multinationals if they are eventually fed back to HQ.

This has usually not been the case. As Henry Chesbrough (the inventor of the concept of ‘open innovation’) of the Haas School of Business at Berkeley explains, Japanese firms have long used Silicon Valley as an innovation platform and launch pad for new ideas – for the American market. The innovations they came up with in Silicon Valley were meant for the American. Maybe more importantly, the organisational innovations they implemented in Silicon Valley (innovation labs, innovation teams, new working modes, etc.…) were also meant to be adapted for American ways of working, not as experiments for how the larger HQ could be reformed. NTT, once Japan’s largest carrier, opened up its innovation lab in Silicon Valley to support its growth in markets outside of Japan. Similarly, KDDI, one of its major competitors, started cooperating with start-ups and innovative firms in the bay area (such as Mozilla Firefox, fuhu, or localmind). Few ideas and innovations originating in America ever found their way back to Japan.

This is beginning to change, however, as firms taking a wider view on the significance of their Silicon Valley dependencies for their global business, including Japan. Increasingly, Japanese firms see their presence in Silicon Valley not only as a mere lynchpin into the American market or observation outpost, but also as laboratory for experiments with relevance for Japan, be it product, service or working mode innovations. Sumitomo Electric, for instance, one of Japan’s largest industrial conglomerates, has started with re-thinking its business model in its Silicon Valley (link). It has changed its organisational structure, particularly its R&D processes and is experimenting with breaking into new, so far untouched business fields, such as Life Sciences. Silicon Valley enables Sumitomo to work quickly and on a smaller scale, but ultimately its business model innovation is meant as a global effort and to be implemented in the overall HQ in Osaka.

As Japanese firms strengthen their presence in Silicon Valley and innovation management is becoming an increasingly pressing concern for boardrooms in Osaka and Tokyo, it will be paramount for firms to get the most out of the innovations originating from their dependencies. Intentionally limiting the reach of their impact to America will become a thing of the past as Sumitomo and others use the innovations from Silicon Valley to also innovate their business models in Japan and globally.

By Markus Winter (link)